Men Really Were Men When It Was a Game

What makes a man truly a man? The answer’s on the diamond. Men really were men when it was a game.

By John G. Stamos

Men Really Were Men When It Was a Game

John G. Stamos

Thinking about the character of the quintessential American male of the first three quarters of the past century, I’m acutely aware of a pulse that encompasses and unifies the rhythms of its myriad manifestations… a bridge that spans vocation and varied mien. That pulse – that bridge – is baseball.

I was just recently watching (for the umpteenth time) one of my all-time favorite sports documentaries. 1991’s When It Was a Game, the powerful and moving HBO Sports masterpiece written by Steven Stern, presents a telling of Major League Baseball history during the period of 1934 through 1957 via 8mm and 16mm home movie films shot both by fans and by the players. The individual homemade films featured in the compilation are in their original color, and their visual clarity and detail are breathtaking and heart-tugging. They deliver to the viewer not only the remarkable mechanics of the game as it was played throughout those most golden of Big League years, and the athletic grace of the men who played it, but the character – the constitution – of those very same legendary heroes.

The internal makeup of such greats as Lou Gehrig, Bob Feller, Joe DiMaggio, Willie Mays, Ted Williams, and many, many more, as reflected so faithfully in their faces by these earnest and plaintive reels would certainly be sufficient to tell this tale, but the addition of the documentary’s audio component adds the bat-on-ball crack that, for me, launched the masterpiece out of the park and directly into the friendly confines of my own heart. A bolstering musical score and narration by orators (and baseball lovers) like James Earl Jones, Jason Robards, and Roy Scheider set the tone of this great work and serve as both its backdrop and an eloquently-guided tour. But what delivered the audio part of the production from my eardrums to my ticker about a million times faster than a Bob Feller speedball are the segments of recorded remembrances by a number of those Big Leaguers themselves. Holy cow, to watch Duke Snider’s facial expressions on a sunny day in Brooklyn in the early 1950s while his 65-year-old voice cracks in 1991 during his recollection of the cumbersome bulk of the Dodger uniforms, or to hear Enos Slaughter, at the age of 75, recounting, also in 1991, the duties and obligations of a player to both his team and to the game, while he smiles at the camera, tips his Cardinals cap, and passes a hand through his prematurely thinning hair on game day in Sportsman’s Park, c. 1940… Holy Cow, indeed. And for that matter, Say Hey, too…

Those voices – The Duke’s and Country’s – and those of so many of their fellow contributing legends featured in When It Was a Game, remembering diamond-hard trials and glories while the camera played across the faces of Major League Baseball of yore… on the blinking of those razor-sharp eyes, on those furrowed brows beneath the bills, on those rakish, gamin grins, on the certitude of graceful, ambling movement that delivered the poetry of a national pastime to an adoring, yearning multitude… there’s a bandwidth of nostalgia in these films that even today carries my own heart and mind far beyond the stands and bleachers, and draws, simultaneously, an inescapable parallel between, and an undeniable convergence of, the character of those men who shaped the game of baseball, and of the men throughout my own life who have in turn shaped me.

My dad, George Stamos, and his brothers, Sam, the eldest, and Pete, the youngest, were rabid baseball fans (as well as Little League players of the game). Growing up in Chicago during the 1920s and 30s, they were faced with the choice of backing one of two home teams: the Cubs or the White Sox. My dad and Uncle Sam sided with the Cubbies, and would ride a series of streetcars from 93rd Street on Chicago’s South Side all the way up to the distal flank of busy Addison Street to pull for Billy Herman, Lon Warneke, and company from within the friendly confines of Wrigley Field. Uncle Pete’s hill to die on was Comiskey Park’s pitcher’s mound, and his team was the White Sox. Although his trip to watch heroes like Frank Grube and Luke Appling was shorter, and needed fewer streetcar transfers than a haul up to the North Side, it required not a single ounce less of conviction than my dad’s and Uncle Sam’s. There was an imposing line of demarcation between these two fraternal camps, and intense fistfights occasionally erupted among the brothers at points of perceived encroachment. These lads were not just ready, they were spoiling to bleed for their teams.

Paying for streetcar rides and game tickets was no mean feat during the years of the Great Depression, particularly for young guys like the Stamos brothers. All three kept jobs from a very early age, and they used their wages to finance game day outings whenever they could. Although they could have easily sneaked in to their respective teams’ venues, they never did. It was important to support their clubs financially as well as morally. Like those great players showcased in When It Was a Game, my dad’s and his brothers’ commitment to Big League Baseball was steadfast and true.

Commitment. Can a man demonstrate the actuality of this element of human character more emphatically than proudly and unquestioningly risking his life for his country? Men of the Greatest Generation did this. Bob Feller of the Cleveland Indians did. Joe DiMaggio and Yogi Berra of the New York Yankees did. Enos Slaughter of the St. Louis Cardinals did. Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox did. (Is it a coincidence that each of these American heroes were among the baseball heroes featured in When It Was a Game? Are you catching this wave?) George, Sam, and Pete Stamos fought in World War II. My dad and my Uncle Sam saw action in the Pacific Theater. My Uncle Pete earned himself a Bronze Star on D-Day on the beaches of Normandy and was gravely wounded for his efforts, so he came home with a Purple Heart, to boot. These brothers are the same three who were willing to bleed for their teams in the 1930s. If I were a better writer, I might be able to create for you a seamless synthesis relating, in fancy words, the parallels between human character as it was demonstrated by heroic men both in times of war on the battlefronts, and in times of peace on the ballfields. But I’m not that better writer, so I’m simply laying these facts on you and once again directing your attention to When It Was a Game. The players you’ll watch and hear there will pull it all together for you. You’ll sense the pulse, and you’ll feel the solidity of that bridge beneath your feet. You’ll understand commitment.

When It Was a Game wasn’t a standalone production. When It Was a Game 2, also written by Steven Stern, followed in 1992 and expanded the years of its coverage to 1928 through 1961. The third and final installment, released in 2000, and again by Stern, focused entirely on MLB’s evolution through the 1960s. The production values and format of the first When It Was a Game continue in these two subsequent works, and 2 and 3 are each just as powerful a testament to the character of the men who played the game as the original. And it was, in fact, in the very late 1960s (maybe ‘69 – but more than likely 1970 – still, close enough, I think) that I had the honor of not only being on the receiving end of two separate demonstrations of that legendary Big Leaguer character, I also got my first real sense of the almost mystical unifying power of baseball as it stitched together, with unbreakable scarlet thread, my childhood understanding of the makeup of the men who played the game, and of my everyday heroes who were my father and his brothers.

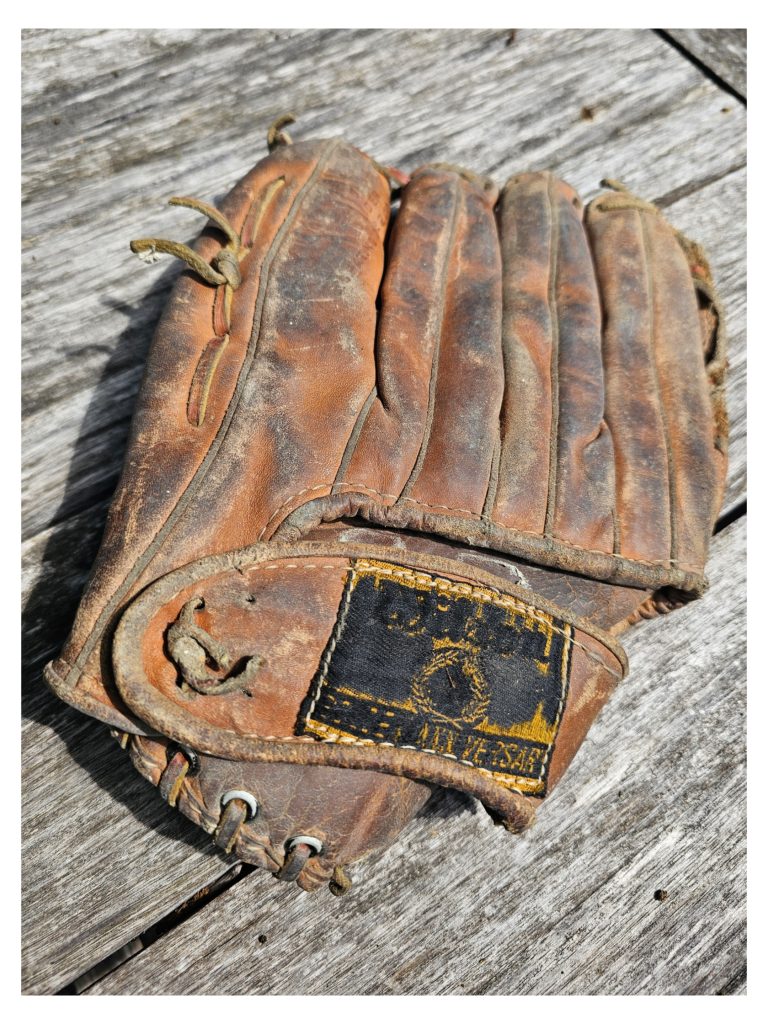

My uncle Pete, the Sox fan, one day took me to a home game at Comiskey when I was five or six (though I honestly do think it was in ’70, but again, close enough to the ‘60s to merit a review of the play). His boys were playing the Minnesota Twins. This was an important fact, as I’d received as a gift earlier that year from my older Cousin John (Uncle Pete’s youngest son) his Wilson “Harmon Killebrew” model baseball glove. The fact that his boy’s old glove was now my own wasn’t lost on my Uncle Pete, and he recognized the relevance of this particular game: Killebrew himself, 13-time Major League All-Star and a Big Leaguer from 1954 through 1975, was the Twins’ third baseman. The gist of the story is this: Harmon Killebrew saw me waving my Wilson around during player warm-ups (we had first row seats not far from the first base line) and he came over, tipped his cap, shook my hand, saw his name on my old Wilson, and asked me if I’d like to see his real signature right there on that glove. I could not speak. After he signed the glove, tousled my hair, shook my Uncle Pete’s hand, and went back to lobbing a hardball around pre-game, the miracle registered with me. And it’s never left my mind. Or my heart. I was in the company of two great men that day in Comiskey Park. There’s a faded autograph on an old hand-me-down Wilson baseball glove that proves it.

Ernie Banks, aka Mr. Cub, Major Leaguer from 1953 through 1971, 14-time All-Star, United States Army veteran, Chicago Cubs shortstop and, later, first baseman, was the most genteel and humble of Major League Baseball royalty. He was also a neighbor. At least he lived in the immediate vicinity of my family’s South Side neighborhood while I was a student at Joseph Warren Elementary School, and while his own son, Joey (four or five years older than I), was, too. My folks were at a parent-teacher orientation event on my behalf at Warren one early fall evening (the year was 1970), and Ernie Banks was there, too. For Joey. At the conclusion of the conference’s initial presentation in Warren’s auditorium, my dad spotted Mr. Cub several seats and rows away, nudged my mom, excused himself, introduced himself to the baseball legend, and asked him if he wouldn’t mind signing an autograph “For my boy, Johnny.”

Not only did he sign the autograph for me that fall evening in 1970 per my dad’s request, he asked after me by name when he ran into my folks at the parent-teacher meet-up the following spring, in 1971. “How’s Johnny doing, Mr. Stamos?” Ernie Banks, one of the greatest, most celebrated players in all of Major League Baseball history, remembered my name. And my dad was bursting at the seams to tell me about it. Those meetings between Mr. Ernie Banks and my father – the intersections of the lives of those two great men, with that greatness, precisely in those moments in time, measured only by the size of their hearts, and defined solely by the depths of their character – was recorded in history by the graceful, swooping lines of a very special signature, in black ink, on the blank back page of a grade school parent-teacher orientation pamphlet. And the sport of Big League Baseball, as it existed during those hallowed years, was its catalyst, its backdrop, its pulse, and its bridge.

The character of the men on the diamond who made the sport of Major League Baseball great during the first three quarters of the 20th century is made of the same stuff as the character of the men who made everyday life in America great at the same time. Heroes to their fans. Heroes to their country. Heroes to their sons. Sometimes, they’re even the same man. I can feel the pulse. I’m standing on the bridge. And I can catch the wave. It’s as easy to field as a lazy pop fly to short center.

“Men Really Were Men When It Was a Game” was originally published in Splice Today (www.splicetoday.com).

“Men Really Were Men When It Was a Game” ©2025. John G. Stamos, Splice Today, and The Renaissance Garden Guy

I hope you enjoyed reading “Men Really Were Men When It Was a Game” as much as I enjoyed writing it. It’s a piece I wrote just last week for Splice Today (www.splicetoday.com), and I’m honored as hell to have it published there. My special thanks go to Splice Today’s publisher, Russ Smith. Russ served as the impetus for the piece, and is truly one of the smartest and finest gentlemen I know.

Cheers, and Happy Gardening!

The Renaissance Garden Guy is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate, The Renaissance Garden Guy earns from qualifying purchases.

Additionally, The Renaissance Garden Guy is a participant in the Bluehost, SeedsNow, and hosting.com (formerly A2 Hosting) affiliate programs. The Renaissance Garden Guy earns a fee/commission each time a visitor clicks on an ad or banner in this site from one of these companies and makes a subsequent qualifying purchase.

Please click here to view The Renaissance Garden Guy Disclosure page.

This is another lovely piece, John. I’m imagining it… Dad and his two brothers as young boys, going to watch their teams…they must have been so excited! I know how excited I was, to be there in the crowd at Wrigley with Tim, our sons, and Mom, cheering on our Cubbies! Going onto the field after the game and taking pictures while “Go, Cubs, go! Go, Cubs, go! Hey Chicago what do you say? The Cubs are going to win today!” BOOMED throughout the park, every single fan singing along! I had goosebumps on my goosebumps!! Those memories are etched in my mind and will forever live on in my heart! (I tried to include one of the pictures here, but wasn’t able to.)

I must have been too young to recall your adventure with Uncle Pete at Comiskey Park, but I sure do remember Dad’s (and Mom’s) excitement after meeting Ernie Banks at Warren. As an adult, I can remember how much Uncle Sam loved going to watch the Cubbies play at Spring Training every year. Poor Uncle Pete. The lone Sox fan. We loved him anyway😉. Go, Cubs, go!!!!!!

Thank you for your lovely remembrances, Tina. It’s amazing how much Chicago big league baseball has impacted our lives, isn’t it? I find the similarities in the character of the men who played the game and the character of the every day heroes who raised us (Dad AND Mom) to be remarkably similar. All of the memories that pertain to major league baseball – and the way that it was played in Chicago – are indelible. Thank you again for your beautiful words.

I am no baseball fan but I did love your story.

Very touching and beautifully written 🌸

Thank you so much, Roxxy. I’m very glad to know that its central themes are points that non-baseball fans such as yourself could also appreciate and find relatable. I thank you kindly for reading it, Roxxy, and for your lovely thoughts and kind words.

So beautiful.Those were the men who inspired so many of us through the years. I once paid a visit to the Basball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Stepping into that building brought back so many memories and dreams that it made my heart skip a beat and brought a tear to my eye. I understand that wave, and I hope that kids today can have that same experience one day.

Thank you so much for your thoughtful words and poignant remembrances, Kevin. The MLB Hall of Fame I think serves as the physical embodiment of the memories and the ideals that made the men of The Greatest Generation – both those on the diamond, and those in our everyday lives – heroes. It should be visited by every American at least once in their lives. Wonderful thoughts, Kevin. Thank you once again for leaving them here.

Your multitudinous interests are truly impressive. You can wear the title “Renaissance Man”with pride.

Oh, wow, Rick – thank you! I really appreciate your reading the piece, and I really appreciate your incredibly kind words. I was always fascinated, and certainly informed, by my father’s and my uncles’ passion for sports. All three were great athletes themselves, and their legendary passion for not only baseball (and their home teams that played it), but other sports as well (football, wrestling, even fencing!), is tied inextricably to local history and my own history, as well. It was an absolute pleasure to write this one. Thanks once again, Rick.

This is a fantastic piece, John. The weaving of baseball and your family history, as well as where these quintessential bits of Americana intersect, are so effective in recreating the spirit and character of all those men that were essential parts of your personal experiences. A wonderful read!

Thank you so much for these lovely, insightful words, Ann. I’m very glad that you found the central theme of the piece so evident, and that it resonated with you. I appreciate your thoughtful analysis of the piece, and your keen perceptiveness. Thank you once again.

That was a moving read, even for those of us who aren’t huge baseball fans. Makes me want to go watch that documentary! Great family tie-in, too.

Thank you so much, Lisa. I’m very happy that you enjoyed it, and I’m really glad to know that its themes transcend the boundaries of baseball fandom. I was hoping this would be the case. Thanks once again for your kind words, Lisa. I’m very grateful.