To See Nature Anew: The Evolution of Animal Art in the 18th & 19th Centuries

The 18th and 19th centuries marked a turning point in the artistic portrayal of animals. Philosophical inquiry and scientific discovery transformed how humans viewed the creatures around them, and artists and audiences alike began to see nature anew.

By R.E. Sample

Humans have been depicting animals in art for tens of thousands of years. From the simple yet sophisticated cave paintings of Chauvet and Lascaux to the bizarre beasts of medieval marginalia, animals have always had a place in our imagination and our art. But in the 18th and 19th centuries, animal depictions in Western art reached unprecedented levels of both accuracy and sentimentality.

Evolving Perceptions:

This artistic shift did not occur in a vacuum. Perceptions of the natural world were changing, and art reflected and propagated these new attitudes.

In earlier centuries, animals were commonly treated as unfeeling instruments that served humanity as laborers, hunters, or food. In art, they were cast chiefly as metaphors for human vices and virtues (rabbits often symbolized lust, ermines represented purity). And when it came to “exotic” creatures, many of which were rarely seen by Western artists, depictions were informed more by imagination and hearsay than observation.

During the Age of Enlightenment, however, this began to change. Thinkers explored the question of animal sentience, and some began to see animals as feeling creatures worthy of both study and compassion. In the 1780s, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham famously wrote, “But a full-grown horse or dog, is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day, or a week, or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”[1]

The Romantic movement played its part, as well; industrialization and urbanization, paradoxically, heightened longing for the natural world even as it drew humanity away from it. Pet ownership, too, was on the rise. Animals (dogs and cats, especially) moved from the yard and street into the home, their presence both providing companionship and signaling status.

Then, in 1859, Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published, dropping a bombshell into the already rapidly evolving public perception of animals. Suddenly people were forced to reckon with the idea that animals might not be so different from us after all. The line between man and beast became blurred and, in the minds of some, disappeared completely.

This change in attitude soon reflected a change in art; animals came to be treated as subjects in their own right and not merely as satirical stand-ins or symbols. Painters and sculptors began to render creatures with new anatomical precision and, just as strikingly, with a heightened tenderness. Animal art soon became a hot commodity; prized livestock were immortalized in paint, and beloved pets increasingly appeared in portraits alongside their masters.

A New Devotion to Observation and Accuracy:

Global exploration in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries brought Western artists and naturalists face-to-face with a wider variety of species than ever before. No longer reliant on travelers’ tales and fanciful rumors, artists were now increasingly able to sketch and study living creatures from direct observation—whether through travel, in zoos and menageries, or by examining preserved specimens.

In an era obsessed with science and progress, it is unsurprising that many animal artists of the 19th century went to great lengths to ensure the accuracy of their paintings and sculptures.

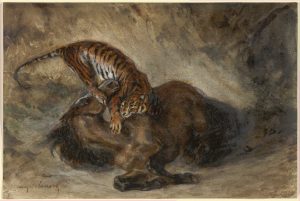

The renowned artist Eugène Delacroix, best known for his painting “Liberty Leading the People,” was fascinated by the natural world, and big cats in particular. He spent long hours in rapt concentration at the Jardin des Plantes zoo in Paris, observing lions and tigers with a passionate intensity. When one of the beasts died, he made sure to be present for the skinning and dissection so that he could study the muscles and tendons firsthand. He channeled this obsessive curiosity into his art, producing dramatic, bloody scenes of animal combat.

Rosa Bonheur, too, based her art on close, first-hand observation. Determined to study the musculature and movement of live animals, she sketched in stockyards, slaughterhouses, and bustling animal markets. To avoid attention in these male-dominated spaces, she even secured a police permit that allowed her to wear men’s clothing. Her masterpiece, “The Horse Fair”—a dynamic depiction of draft horses brimming with power and vitality—was purchased by none other than Cornelius Vanderbilt, who donated it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Later in life, Bonheur kept a small menagerie at her estate, where she raised stags, boar, and even lions, allowing her to study her subjects at her leisure.

The Austrian artist Gabriel von Max, best known for his humorous, often satirical paintings of primates, was equally devoted to his craft. From 1869 to 1873 he maintained a private menagerie of monkeys at his residence in Munich, which he studied, sketched, and photographed. Obsessed with Darwinism and natural history, he also created artistic representations of Neanderthals and other ancient humans, and collected fossils and anthropological specimens with zeal. His vast collection, which included one of the largest skull collections of its time, grew so large that it nearly led him to financial ruin.

Another Austrian artist, Eugen von Ransonnet-Villez, pushed observation to ingenious extremes. While traveling in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), he designed his own custom diving bell. Made of sheet iron and inch-thick glass and weighted down by cannonballs, this small vessel allowed him to remain submerged beneath the sea for hours at a time. From within this cramped observatory, he studied and sketched the aquatic world and its denizens, producing what are widely considered the first artworks made underwater.

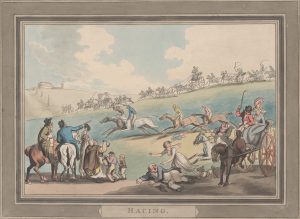

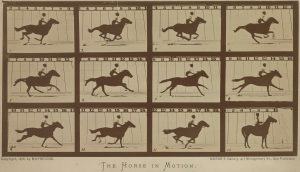

Photography, too, reshaped how artists saw animals. For the first time, living subjects could be frozen mid-stride and examined frame by frame. For example, prior to the 1870s, artists often depicted galloping horses with their legs stretched fore and aft, with no hoof touching the ground, in a pose now known as the “flying gallop.” At the time, no one knew for sure if this was an accurate depiction, as a galloping horse’s legs simply moved too fast for the human eye to register.

This changed in 1878, when the photographer Eadweard Muybridge captured sequential photographs of a running horse for the first time. These now-famous images proved once and for all that the horse does indeed lift all four hooves simultaneously, but only at the moment when its legs are tucked together beneath the body, not when they are outstretched. As a result, artists quickly abandoned the “flying gallop” pose in favor of more accurate, dynamic depictions.

This growing fascination with animal life produced richer, more lifelike art. Closer observation had led to a deeper understanding, and a deeper appreciation, of the natural world. Wild creatures were depicted with increasing realism: alive and in motion, set within their own habitats, and notably free of human presence. The artistic evolution of animals was well underway; they had been transformed from mere curiosities with symbolic meaning into expressive beings with stories of their own.

A Growing Affection:

Victorians craved sentimentality, and animals became ideal vessels for it. Best-selling novels such as Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty and Margaret Marshall Saunders’s Beautiful Joe celebrated animal virtue while decrying human cruelty, and propagated sympathy for animals in the popular imagination.

Visual artists expressed that same sentiment on canvas. Romantic, narrative painters presented scenes in which dogs, horses, and even wild creatures exhibited touching, near-human emotions. Joy and grief, courage and fear, could be read on the faces of their animal subjects.

Landseer, the undisputed king of Victorian animal painting, endowed his subjects, whether they were loyal hounds or majestic Highland stags, with a regal dignity. Charles Burton Barber struck a gentler chord with his sweet domestic scenes, pairing pets with children for maximum cuteness. In contrast, Briton Riviere brought a mournful poignancy to the genre, casting his ever-faithful animals as tragic, noble heroes. Their works were often contextualized by evocative titles—”The Old Shepherd’s Chief Mourner,” “His Only Friend,” “Companions in Misfortune”—that amplified the emotional impact.

Faced with such scenes, viewers were prompted to think of their own furry companions, and perhaps inspired to treat them with kinder regard; one can easily picture a Victorian viewer slipping an extra cut of meat beneath the table or fluffing a pet’s cushion after seeing an image of a faithful hound mourning his beloved master.

These images captivated every social tier in Victorian Britain: inexpensive prints graced parlor walls across the country, and the originals were equally popular among the nobility. Fittingly, the woman who gave her name to the era, Queen Victoria, may have been the most ardent admirer of all. A great animal lover herself, she routinely commissioned portraits of her beloved pets from the most renowned animal painters of the day.

Detractors have long disparaged these narrative animal paintings as overly sentimental, and for much of the 20th century they were dismissed as mawkish and old-fashioned. Yet their power is hard to deny. By portraying animals as loving, noble creatures, Victorian artists helped to normalize compassion toward nonhuman beings, creating enduring images that continue to fascinate and move us today. They taught generations to recognize the spark of shared experience that unites all living things, helping us realize that life, in every form, is worthy of both wonder and compassion.

Sources and References:

[1] Bentham, J. (1823a). An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (Vol. 2). W. Pickering.

Lippincott, L., & Bluhm, A. (2005). Fierce Friends: Artists and Animals, 1750-1900. Merrell Publishers Limited.

Hanks, C. (n.d.). Reframing the Wild: Humans, Animals and Art c.1750 – 1950. ArtUK.org. https://artuk.org/discover/curations/reframing-the-wild-humans-animals-and-art-c-1750-1950

Roe, S. (2011). Briton Riviere: Victorian sentimentality and animals. ArtUK.org. https://artuk.org/discover/stories/briton-riviere-victorian-sentimentality-and-animals

“To See Nature Anew: The Evolution of Animal Art in the 18th & 19th Centuries” ©2025. R.E. Sample and The Renaissance Garden Guy

R.E. Sample is an artist, art historian, and writer. She was born in Scotland to an American military family, and grew up in Texas, North Carolina, and California before settling in Pennsylvania, where she has lived her entire adult life. As a professional artist, she works across a wide range of projects, from oil and charcoal portraits of people and pets to botanical illustrations, murals, and, most recently, a book cover. When not in the studio, she can often be found writing, reading, kayaking, or gardening. With a lifelong passion for art and history, she enjoys sharing her work and insights on social media. Ms. Sample is a regular contributor to The Renaissance Garden Guy (read her most recent previous RGG piece here), and readers can also find her on Instagram at instagram.com/rsample.art and can read her previous work for The Restorationist at https://restorationist.org.uk/the-shifting-english-aesthetic-a-cultural-reflection-from-across-the-atlantic/

The Renaissance Garden Guy is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate, The Renaissance Garden Guy earns from qualifying purchases.

Additionally, The Renaissance Garden Guy is a participant in the Bluehost, SeedsNow, and hosting.com (formerly A2 Hosting) affiliate programs. The Renaissance Garden Guy earns a fee/commission each time a visitor clicks on an ad or banner in this site from one of these companies and makes a subsequent qualifying purchase.

Please click here to view The Renaissance Garden Guy Disclosure page.

Great read. Adds a twist on art history that we often don’t think about. Very informative!

Thank you very much, Lisa! I’m glad you enjoyed it.

I enjoyed reading this thoroughly researched story of animals in paintings. Very informative.

Many thanks.

Thank you, Rick!